CATEGORY: Nutrition

Pregnancy and Infancy

Infancy encompasses the first year of a human life. A healthy, full-term infant is born after successful development during a gestational period of 37–42 weeks. Prior to birth, fetal nutrition is provided directly from the mother’s diet. A woman’s diet during and preceding pregnancy can have a profound effect on the growth and development of her fetus. Unique nutritional requirements during pregnancy include the increased need for iron, folic acid, calcium, and zinc. Calorie (kcal) needs increase during pregnancy by about 300 kcal/day. Weight gain or loss throughout pregnancy is considered a good indicator of nutritional status. Research results show that when dietary and lifestyle counseling is provided, pregnant women are more likely to consume a healthy diet and gain an amount of weight that is within the recommended gestational weight gain guidelines established by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM).

After birth, normal growth and development in infancy depend on the diet provided. Breast milk is considered to be excellent nutrition for infants and nutritionally superior to any available alternative. The recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is that infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life, and that breastfeeding should continue during the introduction of food during the first year. In cases where breastfeeding is contraindicated or is not possible (e.g., the mother is receiving therapy for cancer; the infant has an inborn error of metabolism; in cases of adoption), many types of infant formula are available to provide nutrition that is necessary for the infant to thrive.

At about 6 months of age, infants are usually ready to be introduced to solid foods. This should be done gradually, starting with small servings of simple, soft foods such as rice cereal combined with breast milk or infant formula. Foods should be introduced one at a time at intervals of 2–3 days to assess for food sensitivities or allergies. Small, cut-up pieces of soft food can be offered as the infant becomes more comfortable with solid food, which usually occurs at 8–9 months of age. The introduction of solid foods at 6–12 months of age is primarily educational for infants—allowing them to become familiar with the textures and flavors of food—because during this period their primary nutrition continues to be provided in breast milk or formula.

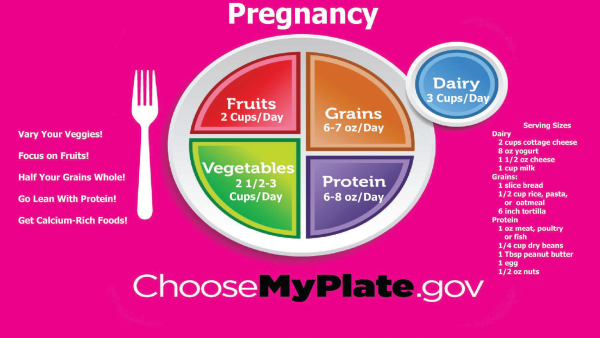

MyPlate recommendations for a pregnancy diet. (U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion)

Dietary Recommendations for Pregnant Women

Eating a well-rounded diet with adequate protein (e.g., about 70 g/day) and a variety of fruits and vegetables is vital for normal fetal development. Calorie requirements increase by about 300 kcal/day, making the average intake goal 2,200–2,900 kcal/day for most pregnant women.

Prenatal supplements that include iron and folic acid are important for pregnant women to take because doing so prevents neural tube defects.

Avoidance of alcohol, tobacco, drugs, and large amounts of caffeine (e.g., > 300 mg/day) is imperative to good fetal health.

Fish and seafood provide the essential nutrient docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which is important in fetal development. Certain types of fish (e.g., shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish) should be avoided because they contain high levels of mercury, which can be harmful to fetal development.

Dietary Recommendations for Infants

Infants require only breast milk or formula for the first 6 months of life. In the first weeks of life, breastfed infants should nurse 8–12 times daily, averaging 15 minutes for each breast. Breastfed infants usually do not require supplementation with formula, although formula can be used when breast milk is unavailable (e.g., if the mother is at work or ill). In some cases, breastfed infants require vitamin D supplementation because breast milk can be deficient in vitamin D, depending on the mother’s dietary intake and metabolism.

Formula-fed infants tend to consume what they require if allowed to feed on demand. Typically, feeding is required every 2–3 hours. Iron-fortified formula is recommended for infants who are fed formula because these infants tend to have inadequate iron reserves and are at risk for iron-deficiency anemia. Neither breastfed nor formula-fed infants require supplemental water because their fluid needs are met by consuming breast milk or formula.

Although breast milk or formula should be the major source of nutrition at 6–12 months of age, solid foods can be gradually introduced. When infants are able to sit independently and reach out for objects, they are ready to start eating solid food. Offering solid food should begin with simple cereal, such as rice cereal combined with warm breast milk or formula. Initial servings should be small (e.g., 1–2 spoonfuls). Infant oatmeal, mashed vegetables, and mashed fruits should be added separately over 2–3-day intervals to allow for assessment of food sensitivities or allergies.

By 8–9 months of age, infants are usually ready to try finger foods (i.e., solid foods cut into small bites). Foods that are hard to chew (e.g., raisins, nuts, popcorn) should be avoided because such foods increase risk of choking.

Common Types of Formulas

About 80% of commercial formulas are cow’s milk that is treated to improve digestibility and make it as similar as possible to breast milk. Hydrolyzed formulas contain milk proteins that are broken down into very small particles to improve digestion in infants who have protein intolerance. Soy-based formulas contain soy protein and are given to infants who are lactose intolerant.

Breastfeeding

Breast milk contains antibodies and cell-mediated immunologic factors that boost the infant’s immune system, providing protection against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); pneumonia; urinary tract infection; bacterial meningitis; gastroenteritis; lymphoma; Crohn’s disease; celiac disease; diabetes mellitus, types 1 and 2; and childhood obesity.

Breastfed infants show a lower incidence of certain allergies and allergic manifestations (e.g., atopic dermatitis) compared with formula-fed infants. Breastfed infants have a lower risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Evidence suggests that breast milk enhances cognitive development.

Breastfeeding is not recommended in the following situations:

-

Mother is receiving treatment for cancer

-

Mother has active tuberculosis, HIV infection, or human T-cellleukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infection

-

Mother has a herpes simplex lesion on her breast

-

Infant has galactosemia, a rare genetic disorder characterized by inability to metabolize any form of animal- or human-derived milk

-

Mother is receiving certain medication (e.g., immunosuppressive or antineoplastic drugs; amphetamines) that is excreted in breast milk and can harm the infant

-

Mother abuses substances (e.g., cocaine, alcohol, methamphetamines)

Research Findings

Probiotic and prebiotic formulas have been devised to encourage the growth of desirable intestinal flora (i.e., bacteria) in formula-fed infants that is similar to that in breastfed babies. These formulas prevent gastrointestinal infection, diarrhea, and onset of allergies. It has also been suggested that the improved gastrointestinal environment that is supported by probiotic and prebiotic formulas aids in the absorption of magnesium, calcium, and iron. In a recent randomized controlled trial, infants who were fed formula containing probiotics and prebiotics tolerated the formula well.

Inadequate gestational weight gain is associated with an increased rate of preterm birth and low birth weight. Excessive gestational weight gain is associated with increased rates of gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia, which can lead to preterm birth. Results of studies show that pregnant women are more likely to gain within the recommended weight range when provided with dietary counseling. Obese women who receive dietary counseling during pregnancy are less prone to high levels of fasting insulin, leptin, and glucose. Counseling is especially effective when it focuses on beliefs regarding body shape and expected gestational weight gain.

Research conducted on mice revealed that a gluten-free diet during fetal life (via the maternal diet) and early infancy reduces the incidence of diabetes and inflammation later in life.

Summary

New parents should become knowledgeable about nutrition for healthy infants. Pregnant women may be at risk for inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain and preterm delivery, requiring dietary counseling and education on guidelines for gestational weight gain. Strict adherence to the prescribed dietary regimen and continued medical surveillance to monitor weight gain will ensure healthy progression of the pregnancy. It is recommended that infants receive breast milk or formula for the first 6 months of life, with the introduction of solid food at 6–12 months. Research suggests that pre and probiotic formulas may help increase infant tolerance.

—Cherie Marcel

References

Lau, Erica Y., et al. “Maternal Weight Gain in Pregnancy and Risk of Obesity among Offspring: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Obesity, vol. 2014, 2014, pp. 1–16, 10.1155/2014/524939.

Moreno, Megan. “Early Infant Feeding and Obesity Risk.” JAMA Pediatrics, vol. 168, no. 11, 1 Nov. 2014, p. 1084, 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3379.

Robinson, S. M. “Infant Nutrition and Lifelong Health: Current Perspectives and Future Challenges.” Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, vol. 6, no. 5, 19 June 2015, pp. 384–389, 10.1017/s2040174415001257.

Stang, Jamie, and Laurel G. Huffman. “Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Obesity, Reproduction, and Pregnancy Outcomes.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, vol. 116, no. 4, Apr. 2016, pp. 677–691, 10.1016/j.jand.2016.01.008.

Symon, B, et al. “Does the Early Introduction of Solids Promote Obesity?” Singapore Medical Journal, vol. 58, no. 11, Nov. 2017, pp. 626–631, 10.11622/smedj.2017024.

Toddlers

Toddlerhood refers to the second and third years of a human life. It is a time of exploration in which the dramatic growth in the first year of life slows, but the motor activity increases. Toddlers are still learning self-feeding skills, such as learning to grasp finger foods, using a spoon and fork, and sipping from a cup. Eating behavior is unpredictable as the toddler experiments with flavors and textures of foods, often choosing to eat only a single type of food for a period of time and subsequently rejecting the chosen food. Although toddlers need to eat 5–7 small meals a day, their appetite naturally decreases (i.e., a processes referred to as physiologic anorexia) after the first year of life. Toddlers frequently become distracted by the surrounding environment while eating and leaving food in inappropriate places because they run off to explore. This can be distressing for the parents/caregivers, who worry that the toddler is not consuming enough food or does not have a healthy diet. Although most toddlers naturally consume enough nutrients for normal growth, monitoring growth helps to determine if they are consuming adequate calories and reduces fears of the caregivers.

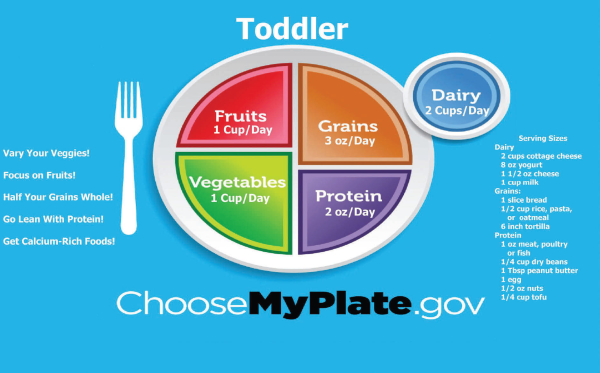

Dietary Recommendations for Toddlers Aged 1–3 Years

Toddlers should eat 5–7 small meals a day. Because lifetime eating habits are established in early childhood, it is vital that caregivers offer a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and proteins throughout the day, keeping in mind that many of the foods will be rejected several times before the toddler decides to sample them.

While eating fruit is recommended, it is best to limit fruit juice intake to 4–6 oz/day of 100% fruit juice from a cup; bottles should only be used for milk or formula. Excessive consumption of juice and other sweetened beverages is linked to dental caries, chronic diarrhea, and imbalanced diets in which fruit juice replaces necessary nutrient intake from other foods. Soda, punch, and other sugary drinks are not recommended under any circumstances.

Milk is a vital source of nutrients, including calcium and vitamin D, during toddlerhood and milk intake should average 2–3 servings (24–30 oz) per day. Drinking whole milk is important until 2 years of age because it provides the fat and cholesterol necessary for brain development. Low-fat milk can be offered after 2 years of age for moderate dietary fat intake of up to 30% of daily calories. It is not necessary or appropriate to restrict fat in the toddler’s diet other than saturated and trans fats that are found in processed foods (e.g., chips, French fries).

Daily intake of 500 mg per day of calcium is recommended for toddlers. 400 international units (IU) per day of vitamin D is recommended. Iron-rich foods are recommended to prevent iron-deficiency anemia, which is a common risk for young children.

MyPlate recommendations for atoddler’s diet. (U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion)

Although introducing a variety of food textures can help toddlers adapt to eating a wider variety of foods, it is important to avoid foods that pose a choking hazard, including foods that are difficult to chew, do not dissolve in saliva, or are hard and round. Common foods that cause choking are whole nuts, hard candy, hotdogs, popcorn, whole grapes, raw fruits and vegetables, and globs of peanut butter. Chewing and mastication skills become more precise throughout toddlerhood, and most children are capable of self-feeding a wide range of foods by the age of 3 years.

Caregivers are encouraged to create a positive eating environment for toddlers, including the following:

-

Allow ample time for the toddler to eat. Eating is a new skill to toddlers and they need time to smell, taste, and touch the food. Encouraging them to eat rapidly increases stress during mealtimes.

-

Be patient when spills and accidents occur because these are part of the toddler’s learning process.

-

Provide utensils toddlers can hold and put into their mouths easily and use break-resistant dinnerware.

-

Create a mealtime environment that is an opportunity for family interaction so toddlers can witness positive eating habits modeled by their caregivers. Toddlers are more likely to try a new food if they see their caregivers and older siblings eating it.

Growth charts are available to monitor toddler weight gain, height, and head circumference in relation to expected norms by age. Although the goal is for the measurements to fall between the 5th and 95th percentile on the growth charts, consistent growth patterns are the best indication of nutritional adequacy in toddlers.

Research Findings

Prebiotics are food components that are not digested in the upper gastrointestinal tract, allowing them to be fermented by intestinal microflora (i.e., bacteria) into probiotic elements, which encourage the growth and activity of more desirable intestinal microflora. Studies indicate that prebiotic foods and supplements prevent the onset of allergies, gastrointestinal infection, and diarrhea and reduce the rate of overall infections in infants and toddlers up to 24 months of age.

Results of many studies show the direct impact of the dietary habits and beliefs of caregivers on the dietary habits and beliefs of their children. Researchers have documented that children tend to make food choices similar to those of both their father and their mother. Evidence suggests that even grandmothers in the toddler’s home environment have a strong influence over the dietary behaviors of their grandchildren. Researchers have documented that the physical activity the family participates in has a direct influence on the activity and dietary choices of the children in the household, which indicates that health promotion interventions need to be family-based in order to be successful.

It is common for children to reject vegetables and favor fruits or cereals. In such situations, researchers suggest that using a little creativity can improve toddler intake of vegetables. Results of a recent study indicate that blending pureed vegetables into other food favorites increased vegetable intake in toddlers.

Researchers report that the results of preliminary controlled trials indicate that multi-micronutrient supplementation in children can positively impact certain aspects of cognition and behavior.

Summary

Parents and caregivers should become knowledgeable about physiologic and dietary needs during toddlerhood. Toddlers should eat 5–7 small meals a day, including a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and proteins, while keeping in mind that many of the foods will be rejected several times before the toddler decides to sample them. Toddlers should be assessed for risk of inadequate and excessive weight gain and growth, and dietary counseling to caregivers may be beneficial. It is important for caregivers to adhere to the prescribed dietary regimen of providing healthy food choices and continue medical surveillance to monitor the toddler’s growth and nutritional status. Research suggests that toddlers are influenced by the dietary habits of family members.

—Cherie Marcel

References

Tran, Bach Xuan, et al. “Global Evolution of Obesity Research in Children and Youths: Setting Priorities for Interventions and Policies.” Obesity Facts, vol. 12, no. 2, 2019, pp. 137–149, 10.1159/000497121.

Wen, Li Ming, et al. “The Effect of Early Life Factors and Early Interventions on Childhood Overweight and Obesity 2016.” Journal of Obesity, vol. 2017, 2017, pp. 1–3, 10.1155/2017/3642818.

Xu, Furong, et al. “A Community-Based Nutrition and Physical Activity Intervention for Children Who Are Overweight or Obese and Their Caregivers.” Journal of Obesity, vol. 2017, 2017, pp. 1–9, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5651117/, 10.1155/2017/2746595.

Preschool-Aged Children

Preschool-aged children (i.e., 3–5 years of age) have mastered the skill of self-feeding and are capable of eating a wide variety of foods. The preschool period is a time of activity, exploration, and learning; typically preschool-aged children show signs of independence and rebellion by around 4 years of age. The period of independence and rebellion is frequently accompanied by finicky eating that is similar to the erratic eating choices and behaviors of toddlers. Fluctuations in the preschooler’s food.

References can cause parents/caregivers to become concerned about whether the child is consuming enough food or has a diet that is healthy enough. There is evidence, however, that children self-regulate their dietary intake to meet their energy needs. If they pick at one meal and do not eat well, they tend to eat more at another. By the age of 5 years, the phase of rebellion passes and most children are willing to try new foods. Monitoring the preschooler’s growth patterns on a growth chart can help to determine if he/she is consuming adequate calories.

Parents/caregivers are encouraged to create a positive eating environment for children, including the following:

-

Keep mealtime pleasant and avoid arguments, which can cause preschool children to attach negative feelings to eating. Children are less likely to try new foods that are introduced in a negative environment.

-

Allow ample time for eating. Children need time to smell, taste, and touch their food. Rushing them can add stress during meal times.

-

Be patient with spills and accidents because they are part of the preschooler’s learning process.

-

Provide utensils that can be held and put into the mouth easily and use break-resistant dishes and glasses.

-

Create a mealtime environment that offers an opportunity for family interaction so preschoolers can witness positive eating habits modeled by their parents/caregivers. Children are more likely to try a new food if they see their parents/caregivers and older siblings eating it.

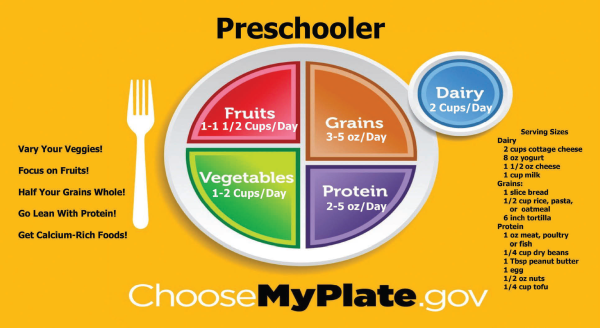

Recommendations for Children 3–5 Years of Age

Calories: 1,000–1,400 kcal/day

Protein: 13–19 g/day

Carbohydrates: 50–60% of total calories consumed/day, with no more than 10% from simple sugars (e.g., white bread, candy, chips)

Fiber: 8–11 g/day

Fat: Total fat intake averaged over 2–3 days should be 20–30% of total caloric intake, with saturated fat consumption comprising less than 10% of total caloric intake. Trans fats, such as those found in many processed foods, should be avoided.

Cholesterol: should not exceed 300 mg/day.

Milk : 2–3servings (24–30 oz) per day

Calcium: 500 mg for children 1–3 years of age, 800 mg/day for children 4–8 years of age.

Vitamin D: 400 international units (IU) per day

Research Findings

Results of many studies show the direct effect of parent/caregiver dietary habits and beliefs on the dietary habits and beliefs of children. Researchers have documented that children tend to make food choices similar to those of both their father and mother. Evidence suggests that even grandmothers in the home environment have a strong influence over the dietary behaviors of their grandchildren. Researchers have documented that the physical activity the family participates in has a direct effect on the activity and dietary choices of the children in the household, which indicates that health promotion interventions should be family- and community-based to be successful, supporting families where they live and work.

Researchers in a recent study investigated the association between family meals, viewing television during meals, and food choices made by children. Results were that children who ate breakfast, lunch, or dinner with their family at least 4 days/week ate more fruits and vegetables than those who did not participate in family meals 4 days/week. Children who rarely or never watched television during family meals were less likely to eat soda and chips.

Researchers report that introducing nutrition and physical activity interventions through child care (or daycare) centers reduces dietary risk factors, such as obesity, for preschool children and their families.

It is common for children to reject vegetable food choices and favor fruits and cereals. In such situations, researchers suggest that using a little creativity can improve vegetable intake during childhood. Results of a recent study found that blending pureed vegetables into other food favorites increased vegetable intake in children.

MyPlate recommendations for a preschooler’s diet. (U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion)

Summary

Parents and caregivers should become knowledgeable about nutrition for healthy preschool children. Preschool children should consume a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins throughout the day. Family dietary counseling may be necessary if children are experiencing inadequate or excessive weight gain and growth. The prescribed dietary regimen should emphasize the importance of healthy food choices and continued medical surveillance to monitor the preschooler’s growth and nutritional status. Research suggests that minimizing television watching results in better dietary choices, and healthy food choices during childhood reduces the risk of obesity.

—Cherie Marcel

References

Khalsa, Amrik Singh, et al. “Attainment of ‘5-2-1-0’ Obesity Recommendations in Preschool-Aged Children.” Preventive Medicine Reports, vol. 8, Dec. 2017, pp. 79–87, 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.08.003.

Towner, Elizabeth K., et al. “Treating Obesity in Preschoolers.” Pediatric Clinics of North America, vol. 63, no. 3, June 2016, pp. 481–510, 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.02.005.

Volger, Sheri, et al. “Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Efforts through a Life Course Health Development Perspective: A Scoping Review.” PLOS ONE, vol. 13, no. 12, 28 Dec. 2018, p. e0209787, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6310279/, 10.1371/journal.pone.0209787.

School-Age Children

School-age children (i.e., 6–12 years of age) are in the stage of development referred to as the latent time of growth. During this period, growth rate slows and developmental changes are gradual as the physiologic foundation is established for the wide-ranging and rapid transformation that occurs in adolescence.

Although school-age children have established habits for food choices and eating meals in their home environment, the introduction of school and other outside activities presents new food options that include school lunches, vending machines, and snacks in the homes of friends. The presentation of new food options can pose a challenge for the parents/caregivers to encourage healthy eating behaviors in their children.

With many children receiving their noon meals from school lunch programs, parent/caregiver knowledge of the food choices offered by the school is important. If the school lunch options are inadequate, parents/caregivers can prepare sack lunches for their children to take to school.

Parent/caregiver influence over children’s choices at breakfast and dinner becomes more important. Results of studies show a strong positive association between breakfast intake and school performance. Research results also show the importance of family-shared mealtimes in developing positive dietary choices in children. The foods provided and eaten by the parents/caregivers strongly influence the foods chosen by their children when away from the home environment.

Because lifetime eating habits are established in early childhood, it is vital that caregivers begin to encourage healthy eating habits in their children at a young age. Encouraging healthy eating habits involves offering a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins at mealtimes and providing healthy food choices for snacks that are appealing and easy to carry.

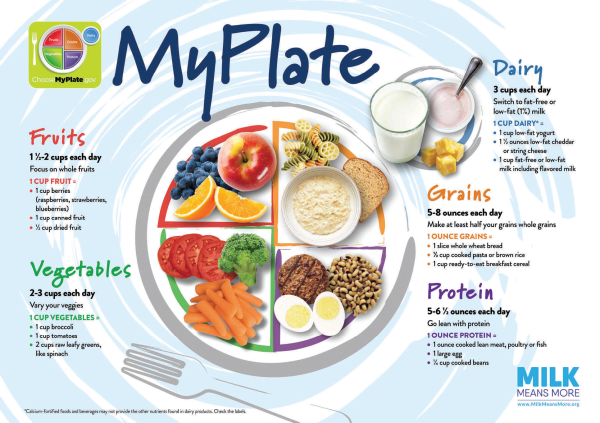

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) produced the MyPlate for Kids, which provides age-appropriate materials and information designed to help children 6–11 years of age increase their knowledge regarding healthy food choices. MyPlate for Kids depicts a pyramid divided into 5 food categories that children should include in their diets: grains, vegetables, fruits, milk, and meat/beans.

Recommendations for School-Age Children

Calories: 1,500–3,000 kcal/day

Protein: 34 g/day

Carbohydrates: 50–60% of total calories consumed daily with no more than 10% from simple sugars (e.g., white bread, candy, chips).

Fiber: 11–17 g/day

Fat: Total fat intake averaged over 2–3 days should be 20–30% of total caloric intake, and saturated fat consumption should be less than 10% of total caloric intake. Trans fats, such as those found in many processed foods, should be avoided.

Cholesterol: should not exceed 300 mg/day.

Milk: 2–3servings (24–30 oz) per day

Calcium: 800 mg/day for children 4–8 years of age; 1,300 mg/day for children 9–13years of age.

Vitamin D: 400 international units (IU) per day

Childhood Obesity

In developed countries, coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of death in both men and women, with death from cancer a close second cause. Diets that are high in saturated fat and cholesterol have been definitively linked to CHD, obesity, and certain cancers (e.g., cancer of the breast, colon, endometrium, gallbladder, esophagus, pancreas, and kidney). Continuing to reinforce positive dietary habits in school-age children is vital to prevent childhood obesity.

Approximately 35% of children in the United States who are 6–19 years of age are overweight or obese. Rates of overweight and obesity are even higher among minority and low socioeconomic status subpopulations.

Childhood obesity is accompanied by many comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular and endocrine dysfunction (e.g., type 2 diabetes mellitus [DM2], dyslipidemia), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), asthma, and orthopedic impairments. The likelihood that obesity will persist into adulthood increases from 20% in obese 4-year-olds to 80% in obese adolescents.

Research Findings

Results of many studies show that the dietary habits and beliefs of parents/caregivers have a direct effect on the dietary habits and beliefs of their children. Researchers have documented that children tend to make food choices similar to those of their fathers and mothers. Evidence suggests that even grandmothers have a strong influence over dietary behaviors in their grandchildren’s homes. Researchers have documented that the physical activity the family participates in has a direct effect on the activity and dietary choices of the children in the household, indicating that health promotion interventions should be family- and community-based to be successful, supporting families where they live and work.

A study investigating the association between family meals, viewing television during meals, and food choices made by the children in the family showed that children who ate breakfast, lunch, or dinner with their families at least 4 days/week ate more fruits and vegetables than those who did not participate in family meals 4 days/week. Children who rarely or never watched television during family meals were less likely to consume soda and chips.

Childhood obesity is a major public health concern in the U.S. and other developed countries. Behavior modification strategies focused on eating a healthy diet and increasing physical activity have produced the best short- and long-term results for weight loss in children. However, there are few treatment programs available to obese children and families who are economically disadvantaged. This is a significant concern considering that rates of overweight and obesity are higher in economically disadvantaged populations. Researchers have suggested that group-based behavioral interventions for the family would lower the expense of treatment and make treatment resources more accessible. Another important focus for intervention is the quality of nutrition standards for foods in schools. Studies have shown that increasing the availability of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products in the school setting can positively affect the food choices of children. Unfortunately, many schools are also equipped with vending machines that provide unhealthy food options, which undermines the effectiveness of the school nutrition programs.

Researchers in a study of children aged 6–13 years living in the inner-city reported that the biggest perceived barrier to physical activity was lack of correct information and that insufficient access to healthy foods acted as a barrier to consuming a healthy diet.

Upon review of a comprehensive obesity prevention program implemented in an underserved Hispanic community, researchers found that, after 2 years, the nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of school staff and students improved significantly. Evidence also suggests that learning activities focused on promoting healthy energy balance and reducing the risk for DM2 in middle school children were most effective if they required peer interaction.

Summary

Parents and caregivers should become knowledgeable about nutrition in healthy school-age children. Children should be encouraged to consume a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, including snacks that are appealing and easy to carry. School-age children may be at risk of inadequate and excessive weight gain and growth, requiring dietary counseling. The prescribed dietary regimen should emphasize the importance of healthy food choices and continued medical surveillance to monitor the growth and nutritional status. Research suggests a positive association between breakfast intake and school performance. Study results also show the importance of family-shared mealtimes in developing positive dietary choices in children.

—Cherie Marcel

References

Arteaga, S. Sonia, et al. “Childhood Obesity Research at the NIH: Efforts, Gaps, and Opportunities.” Translational Behavioral Medicine, vol. 8, no. 6, 21 Nov. 2018, pp. 962–967, academic.oup.com/tbm/article/8/6/962/5134051, 10.1093/tbm/iby090.

Kim, Hee Soon, et al. “What Are the Barriers at Home and School to Healthy Eating?” Journal of Nursing Research, vol. 27, no. 5, Apr. 2019, p. 1, 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000321.

Pandita, Aaakash, et al. “Childhood Obesity: Prevention Is Better than Cure.” Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, vol. 9, Mar. 2016, p. 83, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4801195/, 10.2147/dmso.s90783.

Adolescents

Adolescence marks the onset of puberty, which is the final growth spurt of childhood. This phase of development is a time of accelerated and significant physical changes. The adolescent body is maturing and developing sexual characteristics due to the release of estrogen and testosterone. The characteristic changes vary widely in timing and manifestation among adolescents. Girls tend to develop earlier and more rapidly than boys, but weight and height in boys eventually surpass that of girls.

Adolescence can be a distressing stage of life due to the physical transformation of the body. In some cases, girls become insecure about their degree of developing breasts and hips and boys feel inadequate and impatient if their height and weight are less optimal than their peers. Psychosocial development during adolescence is significant, and a sense of growing independence leads adolescents to begin looking to their friends rather than family members for affirmation. The pressure to be accepted by peers is strong and affects the adolescent’s perceptions of style, social norms, physical activity, and dietary habits.

Although the influence of the adolescent’s parents/caregivers largely shifts to a focus on peer influence, the role of family support during this growth period should not be underestimated. Most adolescents eat their initial meal of the day at home. Results of studies show a strong positive association between breakfast intake and school performance. Many adolescents eat the majority of their dinners at home even though their evening activities outside the home have increased. Research results show the importance of family-shared, television-free mealtimes in developing positive dietary choices in adolescents. Foods provided and eaten by the family remain a strong influence on the adolescent’s choice of foods outside of the home.

Dietary Challenges for Adolescents

Eating Disorders. Because of the rapid growth and changes that occur during adolescence, the body’s demand for energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals increases. The heightened hunger that adolescents experience can result in consuming unhealthy snacks (e.g., chips, sodas, candy bars) that have poor nutritional value and are readily available in vending machines, fast-food restaurants, and certain friends’ homes. Many girls begin to gain weight during adolescence, which can cause them to feel insecure even if the weight gain and fat deposits are simply due to normal maturation. Social pressure to be thin frequently drives affected girls to self-impose a poorly planned diet for weight loss. For many, this is the beginning of an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The harmful effects of severe dieting and eating disorders during adolescence can extend into adulthood and cause infertility, metabolism dysfunctions, and difficulty with weight control. Treatment for eating disorders involves psychological and nutritional counseling, either individually or in group settings, and hospitalization is necessary in some cases to manage fluid imbalances, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, protein and energy malnutrition, and/or depression.

Anorexia nervosa develops when a person consumes too few calories to support normal body functions and growth. Due to an intense fear of weight gain and negative self-image, persons with anorexia nervosa will starve themselves and/or exercise excessively, losing more weight than is healthy.

Bulimia also occurs as the result of irrational fear of weight gain and/or body dysmorphia (i.e., misperception of body image). A person with bulimia may eat large amounts of food and induce vomiting or abuse laxatives in an attempt to avoid weight gain.

Obesity. In developed countries, coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of death in both men and women, with death from cancer a close second. It has been speculated that 10–70% of cancer-related deaths are preventable by alterations in diet. Diets that are high in saturated fat and cholesterol are definitively linked to CHD, obesity, and certain cancers (e.g., cancer of the breast, colon, endometrium, gallbladder, esophagus, pancreas, and kidney). Continuing to reinforce positive dietary habits in children is vital to prevent childhood obesity. Current statistics show that about 35% of children in the United States who are 6–19 years of age are overweight or obese. Rates of overweight and obesity are even higher among minority and low socioeconomic status subpopulations. Childhood obesity is accompanied by many comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular and endocrine dysfunction (e.g., diabetes mellitus, type 2 [DM2], dyslipidemia), obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, and orthopedic impairments. The likelihood of obesity persisting into adulthood increases from 20% in obese 4-year-olds to 80% in obese adolescents.

MyPlate recommendations for a preschooler’s diet. (U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion)

Research Findings

Results of a study investigating the association between family meals, viewing television during meals, and food choices made by the children in the family showed that children who ate breakfast, lunch, or dinner with their family at least 4 days/week ate more fruits and vegetables than those who did not participate in family meals 4 days/week. Children who rarely or never watched television during family meals were less likely to consume soda and chips.

Obesity is a major public health concern in the U.S. and other developed countries. Behavior modification strategies that focus on eating a healthy diet and increasing physical activity have produced the best short- and long-term results for weight loss in children and adolescents. However, there are few treatment programs available to obese children and their families who are economically disadvantaged. This is a significant concern because rates of overweight and obesity are higher in this subpopulation. Researchers suggest that behavioral interventions that are group-based would lower the expense of treatment and make treatment resources more accessible for families with limited funds. Another important focus for intervention is the quality of nutrition standards for food in schools. Results of studies show that increasing the availability of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products in the school setting can positively affect the food choices that children make. Unfortunately, many schools also have vending machines that provide unhealthy food options that undermine the effectiveness of the school nutrition programs.

Recommendations for Adolescents

Calories: 1,500–3,000 kcal/day

Protein: 46 g/day for girls and 52 g/day for boys

Carbohydrates: 50–60% of total calories consumed each day, with no more than 10% from simple sugars (e.g., white bread, candy, chips)

Fiber: 36–38 g/day

Fat: Total fat intake averaged over 2–3 days should be 20–30% of total caloric intake; saturated fat consumption should be less than 10% of total caloric intake. Trans fats, such as those found in many processed foods, should be avoided

Cholesterol: should not exceed 300 mg/day

Milk: 2–3 servings (24–30 oz) per day.

Calcium: 1,300 mg/day

Vitamin D: 400 international units (IU) per day

Activity: 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity 5 times a week.

Adolescence is a phase of childhood development that is strongly associated with the onset of eating disorders, particularly in adolescent girls. Early onset of puberty is a well-established risk factor for restrictive dieting in adolescent girls. This reinforces the understanding that adolescents are profoundly influenced by the acceptance of their peers. As a girl’s body changes, she becomes aware of the other girls in her age group. Early maturation can lead to feelings of conspicuousness and insecurity about the body. Study results show that girls who develop an eating disorder in adolescence have a high likelihood of continuing to have an eating disorder in adulthood. Evidence also indicates that eating disorders and unhealthy dieting can result in difficulty with metabolism and weight control, including obesity, later in life. Researchers suggest that intervention strategies should target the peer groups of adolescent girls rather than focusing exclusively on the affected individual because motivation to change eating habits frequently stems from peer influence. Identifying the eating habits of the peer group can help formulate strategies to assist the affected individual in overcoming the eating disorder, potentially preventing future complications.

Research confirms that adolescents who embrace healthy dietary practices and participate in physical activity are less likely to exhibit health risk behaviors (e.g., substance use), have a more accurate self-perceived health status, are more optimistic and satisfied with life, and have a reduced incidence of depressive symptoms. Additionally, the more obesogenic lifestyle risk factors an adolescent exhibits, the poorer his or her quality of life tends to be and continues to be into adulthood.

Summary

Individuals should become knowledgeable about nutrition in adolescents. Adolescents should consume a variety of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, lean proteins, and healthy fats, while minimizing simple sugars and highly processed foods. Adolescents may be at risk for inadequate and excessive weight gain and growth; possibly requiring dietary counseling. A prescribed dietary regimen may be necessary to emphasize the importance of healthy food choices. Research suggests that adolescents who embrace healthy dietary practices are less likely to struggle with obesity later in life.

—Cherie Marcel

References

Ajie, Whitney N., and Karen M. Chapman-Novakofski. “Impact of Computer-Mediated, Obesity-Related Nutrition Education Interventions for Adolescents: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 54, no. 6, June 2014, pp. 631–645, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1054139X13008422, 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.019.

Golden, N. H., et al. “Preventing Obesity and Eating Disorders in Adolescents.” PEDIATRICS, vol. 138, no. 3, 22 Aug. 2016, pp. e20161649–e20161649, 10.1542/peds.2016-1649.

Hilger-Kolb, Jennifer, et al. “Associations between Dietary Factors and Obesity-Related Biomarkers in Healthy Children and Adolescents - a Systematic Review.” Nutrition Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, Dec. 2017, 10.1186/s12937-017-0300-3.

Øen, Gudbjørg, et al. “Adolescents’ Perspectives on Everyday Life with Obesity: A Qualitative Study.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, vol. 13, no. 1, Jan. 2018, p. 1479581, 10.1080/17482631.2018.1479581.

Todd, Alwyn, et al. “Overweight and Obese Adolescent Girls: The Importance of Promoting Sensible Eating and Activity Behaviors from the Start of the Adolescent Period.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 12, no. 2, 17 Feb. 2015, pp. 2306–2329, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4344727/, 10.3390/ijerph120202306.

Zalewska, Magdalena, and Elżbieta Maciorkowska. “Selected Nutritional Habits of Teenagers Associated with Overweight and Obesity.” PeerJ, vol. 5, 22 Sept. 2017, p. e3681, 10.7717/peerj.3681.

Adults and Older Adults

Over the past century, life expectancy has increased. Since 1870, the number of persons over the age of 65 has increased from 1 million to 32 million, and is expected to reach 71 million by the year 2030. Ten percent of older adults are 85 years of age and older, making this the fastest growing age group among the aging population.

As the human body ages, physiologic changes occur that can affect nutritional status. For example, muscle mass and bone density diminishes; changes occur in the perception of flavor, taste, and odor; hearing and vision become less acute; cognitive capacity diminishes; and circadian rhythms shift, which affects sleep/wake patterns and overall energy. Organ function declines, and the gastrointestinal (GI) system slows, which affects the body’s ability to digest, metabolize, and absorb nutrients, and inhibits efficient elimination of waste.

Although age-related changes occur gradually, they tend to accelerate after 55 years of age. The incidence of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), and osteoporosis increases in older adults. Researchers consistently report that these chronic conditions are directly correlated to dietary habits, exercise, and stress management. Initiating and maintaining healthy dietary and other lifestyle behaviors can prevent or postpone the onset of a chronic disease, or slow its progress.

Signs and Symptoms of Dementia

In the United States, dementia affects approximately 14% of persons over 71 years of age, and is the leading cause of dependence among older adults. Individuals with dementia experience variable changes in appetite, nutritional patterns, and the ability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADLs), such as shopping for and preparing food.

Signs and symptoms of dementia include the following:

-

Memory loss and disorientation, which often manifests by pacing and wandering

-

Communication impairment

-

Inability to recognize persons or things that were once familiar

-

Inability to learn, comprehend, or reason

-

Significant weight changes

-

Mood swings, personality and behavioral changes (e.g., aggression, suspicion, agitation), and insomnia

-

Hallucinations and delusions

-

Loss of independence due to inability to perform ADLs

Dietary and Lifestyle Recommendations that Promote Healthy Aging

It is important to consume enough calories to support general health. The recommended minimum calorie intake per day is 1,500 calories for men and 1,200 calories for women.

In order to provide adequate nutrients to support overall health, it is important to choose nutrient-dense foods such as whole grains, fresh fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts, lean proteins (e.g., fish, chicken breast), and low-fat dairy products. The American Heart Association (AHA) has outlined dietary guidelines:

Recommendations for Adults

Calories: 2,000 calories a day for women and 2,500 for men

Protein: 56 g/day for men; 46 g/day for women

Carbohydrates: 45-65% of total calories consumed daily with no more than 10% from simple sugars (e.g., white bread, candy, chips).

Fiber: 25-30 g/day

Fat: Total fat intake averaged over 2–3 days should be 20–35% of total caloric intake, and saturated fat consumption should be less than 10% of total caloric intake. Trans fats, such as those found in many processed foods, should be avoided.

Cholesterol: should not exceed 300 mg/day.

Milk: 3 cups or 732 mL/d per day

Calcium: 1,000 mg/day

Vitamin D: 400 international units (IU) per day

Consume a diet that is rich in vegetables and fruits. Eating a variety of deeply-colored fruits and vegetables (e.g., spinach, carrots, berries) should be emphasized. Drinking fruit juice should not be encouraged because it does not provide the fiber of whole fruit and has a higher calorie content per serving.

Choose whole-grain, high-fiber foods. Research results have shown that a high intake of dietary fiber is associated with lower risk for CVD and lower all-cause mortality, although the inverse relationship with all-cause mortality decreases with age. At least half of the grains consumed should be whole grains.

Consume fish, especially oily fish, at least twice a week. Fish is a great source of the unsaturated fat omega-3, which has many health benefits, including reduced risk for CVD.

Dementia and Nutrition

Provide familiar foods that the person has previously liked.

Provide small, frequent meals.

Enable self-feeding for as long as possible by providing finger foods and utensils that are easily held (e.g., a fork with a large handle), and/or assisting with eating.

Fortify foods with whole milk or protein supplements, and provide high-calorie snacks if calorie consumption is inadequate.

Serve food at a comfortable temperature (e.g., not excessively hot or cold).

Provide a dining area that is familiar and quiet, with adequate lighting.

Follow a consistent meal schedule.

Encourage physical activity, if possible, to stimulate appetite and circulation.

Limit intake of saturated fat, trans fat, and cholesterol. Choose lean meats. Choose dairy products that are fat-free (i.e., skim), 1% fat, or low-fat. Limit consumption of partially hydrogenated fats. It is currently recommended that dietary fat and cholesterol intake should be limited as follows:

-

Total dietary fat < 35% of total caloric intake but not less than 20%

-

Saturated fat < 7% of total caloric intake

-

Trans fat < 1 % of total caloric intake

-

Cholesterol < 300 mg/day

Minimize intake of beverages and foods that contain added sugar.

Choose and prepare foods with little or no salt. Sodium intake should not exceed 2,300 mg/day.

For those who consume alcohol, moderate consumption is recommended. It is recommended that men limit alcohol intake to 2 drinks/day and women limit alcohol intake to 1 drink/day, preferably consumed with meals. 1 drink = 12 oz of beer, 4 oz of wine, or 1 and a half oz of 80 proof liquor.

MyPlate recommendations for an older adult’s diet. (U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion)

Older women are at an increased risk for developing osteoporosis due to the drop in estrogen that occurs with menopause. Additionally, many older persons do not consume or absorb (i.e., from the sun) enough vitamin D each day. Among its many functions, vitamin D is vital for the absorption of calcium. Consuming adequate calcium and vitamin D can help to maintain healthy bones in aging persons.

The recommended daily intake of calcium is at least 1,200 mg/day. Sources of calcium include dairy products, fish with bones, broccoli, and legumes.

It is recommended that adults aged 51–70 years should take 400 international units (IU) of vitamin D/day, and adults over age 70 should take 600 IU/day. Most vitamin D is absorbed through the skin from exposure to sunlight. Food sources of vitamin D include salmon, egg yolks, cheese, and dairy products that have been fortified with vitamin D.

Regular physical activity for 30–60 minutes at least 5 times a week is recommended to maintain muscle mass and bone density, and to promote cardiovascular health.

Research Findings

The Mediterranean diet, originally based on the dietary patterns of persons living in the Mediterranean basin during the 1960s, replaces saturated fats with unsaturated fats (predominantly olive oil); encourages consuming a variety of fresh fruits and vegetables, and foods that are minimally processed; and limits consumption of dairy products, eggs, and red meat. Emphasis is placed on using seasonally fresh and locally grown foods. Potential benefits to following the Mediterranean diet include weight loss, reduced pain and swelling for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, and lower risk for cardiovascular events and cancer. Along with the physical benefits of following the Mediterranean diet, there is evidence that psychological well-being is enhanced. Researchers have reported that the Mediterranean diet exhibits potential for protection against age-related cognitive decline.

Evidence has shown that daily intake of the recommended amount of vitamin D and calcium can result in improvement in bone mineral density in the skeletal system of postmenopausal women. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that the combination of adequate calcium and vitamin D, along with increased physical activity, can decrease the risk for osteoporosis later in life.

The linolenic metabolites eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which can be found in fatty fish (e.g., salmon, mackerel), walnuts, soybeans, and flax seeds, have been shown to play a protective role against dementia, CVD, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis, which may be due to their anti-inflammatory activity.

According to researchers, consuming egg yolks can increase macular pigment concentration in older adults who are taking cholesterol-lowering statins. Results of other studies show that eggs contain highly bioavailable lutein, which is a carotenoid that is believed to prevent age-related macular degeneration and cataracts. Although egg yolks are a significant source of cholesterol, research indicates that eating 1–2 eggs/day does not significantly affect the blood lipid profile and does not appear to increase the risk for CVD.

Summary

Individuals should become knowledgeable about diet and aging. Older adults are at risk for CVD, DM2, osteoporosis, dementia, and malnutrition. In order to receive adequate nutrients to support overall health, it is important for older adults to choose nutrient-dense foods such as whole grains, fresh fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts, lean proteins, and low-fat dairy products. A prescribed dietary regimen emphasizing the importance of adherence to the plan of care and continued medical surveillance to monitor nutritional and overall health status may help reduce risk factors associated with aging. It is especially important for family and caregivers to understand the signs and symptoms of dementia and make sure these individuals are receiving adequate nutrition. Research suggests that following the Mediterranean diet, receiving adequate vitamin D and calcium, EPA and DHA fatty acids intake, and eating 1–2 eggs per day may be dietary factors that contribute to healthy aging in older adults.

References

Bales, Connie W, and Kathryn N Porter Starr. “Obesity Interventions for Older Adults: Diet as a Determinant of Physical Function.” Advances in Nutrition, vol. 9, no. 2, 1 Mar. 2018, pp. 151–159, 10.1093/advances/nmx016.

Batsis, John A. “Obesity in the Older Adult: Special Issue.” Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, vol. 38, no. 1, 2 Jan. 2019, pp. 1–5, 10.1080/21551197.2018.1564197.

Batsis, John A., and Alexandra B. Zagaria. “Addressing Obesity in Aging Patients.” The Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 102, no. 1, 1 Jan. 2018, pp. 65–85, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5724972/, 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.007.

Zhou, Lin, et al. “The Impact of Changes in Dietary Knowledge on Adult Overweight and Obesity in China.” PLOS ONE, vol. 12, no. 6, 23 June 2017, p. e0179551, 10.1371/journal.pone.0179551.